By Zhaolan Wang

The DFL’s 2023 education law boosted school funding with increased special education subsidies and put $300 million toward early childhood education programs.

Minnesota recently ranked 19th among the states in the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s long-running education quality rankings, a drop from sixth place less than a decade ago raised concerns about the effectiveness of funding and the recovery of education after the pandemic. Experts said post-pandemic recovery efforts remain inadequate, with teacher shortages and unequal distribution of resources persisting.

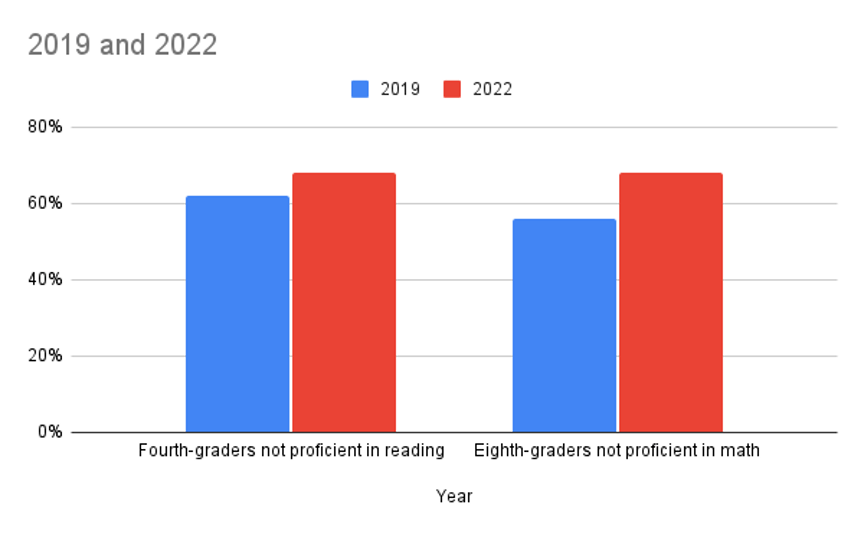

National benchmarks showed that in 2022, Minnesota fourth graders’ reading proficiency fell below the national average for the first time in history, according to the Minnesota Reformer.

Data is from Annie E. Casey Foundation.

“We just did not have an aggressive COVID recovery plan,” said Joshua Crosson, executive director of Minnesota education nonprofit EdAllies.

Michele Mazzocco, a University of Minnesota professor and researcher in the Institute of Child Development, said a downward turn doesn’t surprise her, but a drop from six to 19 does.

“In the last decade, I think it is not just because of the pandemic,” Mazzocco said.

The Impact from COVID-19:

The test paper was positive for Covid-19, photo taken in the year of 2020.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz closed in-person education across the state in March 2020 as the pandemic took hold, according to Emergency Executive Order 20-19. Closing schools was especially difficult for administrators living in rural communities where a majority of parents wanted schools open, said Deb Henton, executive director of the Minnesota Association of School Administrators.

“Changes and issues during and after COVID-19 have to be done,” Mazzocco said. “There may be more than I’m going to mention, but some of the issues that I am aware of and concerned about are the limited socialization opportunities that there were during the pandemic.”

Schools remained closed or in remote instruction here longer than the national average during the pandemic and more than half of Minneapolis students missed 10% or more of school days in 2022, according to at least one estimate, according to the Minnesota Reformer.

Julia Christenson, a the University of Minnesota, majored in data science said the pandemic happened when she was in high school.

“I guess during the pandemic, it was hard to stay focused on school sometimes, but I think it improved my organization skills because I had to write down what I needed to do every day,” Christenson said.

Americans spent more time at home in 2023 than they did before the pandemic, according to data from the American Time Use Survey released in June. About 35% of people did some or all of their work at home in 2023, compared to just 24% in 2019.

Kaylie Sirovy, a University of Minnesota student said the pandemic broke her learning habits.

“I learned to procrastinate. I could not get out of procrastinating,” Sirovy said. “It’s hard to focus because in my head it’s almost kind of like TV, like YouTube style and I have YouTube in the background whenever I’m doing homework, so it feels like I don’t need to pay attention.”

The education gap:

Students from low-income families tend to score lower on standardized tests, resulting in a wide achievement gap. Schools in economically disadvantaged areas are challenged by a lack of resources, inexperienced teachers, and high dropout rates, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Minneaplis file.

Mazzocco said there isn’t just one reason why there is this education gap.

“Many of them have to do with the resources that are unfortunately tied to family and community socio-economic status, the other factors have to do and you know those resources include access, not only to high-quality schools, but to centers and other resources that support child development,” Mazzocco said.

Statistics for the 2023 to 2024 school year show a whopping 86% of K-12 public schools in the United States documented challenges in hiring teachers, according to Audacy News. Minnesota is estimated to have 18,000 job openings for elementary school teachers and 14,000 for high school teachers over the next decade.

“There are differences in educational opportunities across states because states have their different policies and funding mechanisms. There are differences across the types of schools. There are also differences in teacher preparation. Of course, the shortage of teachers is a big problem,” Mazzocco said. “The problem is we should also focus on training early childhood educators and then the other community resources that allow children to have access to medical care, family support, child care and support for working families.”

How might this affect Minnesota’s workforce?

Lower levels of K-12 proficiency, especially in math, reading and science, can lead to lower skill levels in the workforce. For example, basic literacy and numeracy skills are critical for most jobs, and businesses may struggle to find qualified employees, especially in high-demand technology, health and trade fields, according to the bank file.

“Across states, there are differences in terms of whether kindergarten is mandatory. I think only 19 or 20 states require that children go to kindergarten. So, state policies, and local policies are important,” Mazzocco said.

Income-related education gaps can widen economic inequality.

Students from low-income or rural backgrounds face greater challenges, which often lead to lower high school graduation rates and less postsecondary achievement. As adults, these individuals may face higher rates of unemployment or remain in low-paying jobs, lowering overall state income levels, according to the file.

Night view in Minneapolis, photo taken in 2024.

Child care is unaffordable for far too many families across the United States. States have significant flexibility under the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) to define who is eligible to receive child care assistance and what level of copayment is required, according to the Center for American Progress Action Fund.

The child care subsidies pay childcare providers to care for children from low-income families, giving them more opportunities to thrive as learners, according to the Minnesota Department of Children, Youth, and Families.

Minnesota will increase funding for the early learning scholarships program by $252 million from 2024 to 2025, with another $58.9 million increase from 2026 to 2027. The state is also expanding scholarship eligibility to children ages zero to five and increasing the number of subsidized child care slots by more than 50%, according to the CAP.

Minnesota will invest $316 million over two years in a new grant program that will enable childcare centers to increase wages by an estimated $400 per month for a full-time employee, according to the CAP.

The federal poverty level is a government-defined income threshold that determines whether a household is considered to be living in poverty, and varies based on the number of people in the household, according to HealthCare.

Source list:

- American Time Use Survey Summary

- Child Care Assistance Program

- Federal poverty level (FPL)

- Joshua Crosson: executive director of Minnesota education nonprofit EdAllies.

- States Are Taking Action To Address the Child Care Crisis

- Michele Mazzocco: UMN Professor in Institute of Child Development

- Kaylie sirovy

- Julia Christenson

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s

- The MPR News: 6 facts about Walz’s education track record in Minnesota

- Teacher shortage continues to plague Minnesota in 2024 but the state has a plan to increase numbers

留下评论